Unemployment is known to have negative effects on society, for example, through increased need for social and health services, and higher unemployment benefit costs. At an individual level, this highlights the financial challenges resulting from loss of earnings, and their connection on many aspects of life. Prolonged unemployment increases the risk of deterioration in the human and social capital among job seekers. Studies have shown that long-term unemployment negatively affects the earning potential of individuals after they have found employment, compared to individuals who have been unemployed for only a short period of time before being re-employed (Nichols, Mitchell, Lindner 2013). Unemployment increases the risk of ill health and exclusion from the labour market; the unemployed person loses the positive psychosocial effects of work, furthermore, unemployment increases the use of health services (Kerätär 1995; Bouget, Vanhercke 2016).

Long-term unemployment a particular challenge in Helsinki-Uusimaa and Helsinki Metropolitan Area

A long-term unemployed person is someone who has been continuously unemployed for 12 months or more. According to the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland, long-term unemployment is a particular problem in the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region. According to the Ministry, long-term unemployment particularly affects people over 50 years of age and those with primary education only. People who have been unemployed for a long time are also more likely to have diagnosed disabilities or long-term illnesses than other unemployed people. According to statistical data, long-term unemployed people’s participation in education and training has been rare before the unemployment period became prolonged (Maunu, Räisänen, Tuomaala 2023).

As well as disrupting long-term unemployment, it is important to consider how we can prevent future long-term unemployment and the accumulation of problems. Should more attention be paid to the integration of young people into education and employment in order to prevent the development of long-term unemployment at a later age, when statistics show that it is more difficult to find work?

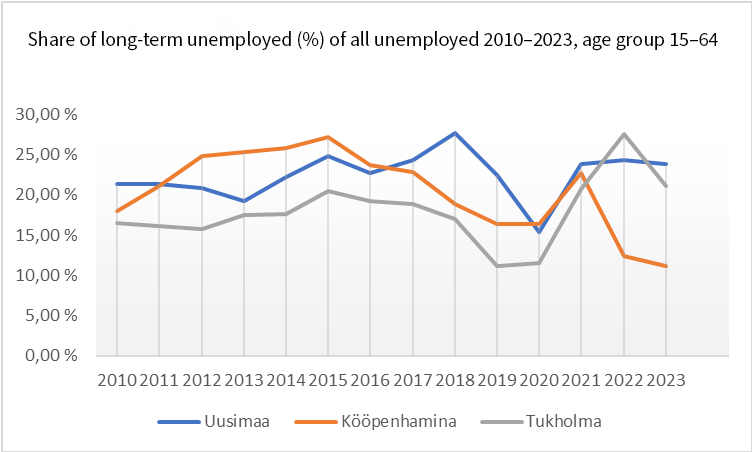

According to employment statistics, 37–38% of unemployed jobseekers in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area have been long-term unemployed during 2024, and the figures for the whole of the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region are in line with the capital region. Nationally, the corresponding figure for 2024 is in the range of 31–35% (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland Employment Statistics). These figures underline the challenge of long-term unemployment, especially in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. In a Nordic comparison, the share of long-term unemployed in the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region was on a good downward trend before the COVID pandemic but, since then, the share has become higher in Helsinki-Uusimaa than in the comparison regions (Figure 1).

Half of the long-term unemployed have never really integrated to working life

Long-term unemployment after adolescence cannot be explained solely by lack of education or employment before the age of 30. For example, illness or sudden regional economic restructuring may lead to longer unemployment without it being linked to youth. However, it should be noted that around half of all long-term unemployed have never properly integrated into the labour market (National Audit Office of Finland 2011). We also know that long-term exclusion from employment and education at a young age (NEET status) negatively affects later employment and increases the risk of periods of unemployment (Redmond, McFadden 2023; Hiilamo, Määttä et al. 2017).

A long-term unemployed person is someone who has been continuously unemployed for 12 months or more. According to the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland, long-term unemployment is a particular problem in the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region. According to the Ministry, long-term unemployment particularly affects people over 50 years of age and those with primary education only. People who have been unemployed for a long time are also more likely to have diagnosed disabilities or long-term illnesses than other unemployed people. According to statistical data, long-term unemployed people’s participation in education and training has been rare before the unemployment period became prolonged (Maunu, Räisänen, Tuomaala 2023).

As well as disrupting long-term unemployment, it is important to consider how we can prevent future long-term unemployment and the accumulation of problems. Should more attention be paid to the integration of young people into education and employment in order to prevent the development of long-term unemployment at a later age, when statistics show that it is more difficult to find work?

According to employment statistics, 37–38% of unemployed jobseekers in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area have been long-term unemployed during 2024, and the figures for the whole of the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region are in line with the capital region. Nationally, the corresponding figure for 2024 is in the range of 31–35% (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland Employment Statistics). These figures underline the challenge of long-term unemployment, especially in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. In a Nordic comparison, the share of long-term unemployed in the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region was on a good downward trend before

the COVID pandemic but, since then, the share has become higher in Helsinki-Uusimaa than in the comparison regions (Figure 1).

Improving young people’s labour market position

Long-term unemployed young people have described, within a survey setting, the obstacles they face when looking for a job and becoming employed. The survey interviews revealed young people’s passive attitudes towards finding out about things on their own. This suggests difficulties in coping with planning for the future, which can last for years without outside help. The survey also revealed young people’s lack of knowledge about working life required for job seeking. In addition, young people talked about a lack of jobs in their own sector, and their lack of skills were cited as barriers to job search and employment. The survey also identified a group of young people for whom seeking work and employment were not a priority for various reasons (Ylistö 2015).

Based on these studies, it is essential to focus on strengthening cooperation with working life during studies, and on a smooth transition to working life. Making use of data on future skills requirements and cooperation between educational institutions, employers, and organisations producing predictive data will help ensure that young people graduate with skills that match labour market needs. Employers should be encouraged to hire recent graduates, for example, by developing induction pathways to support them.

Secondly, we must ensure that all young people complete upper secondary education, because education protects them from unemployment. At the same time, automation and digitalisation, among other things, have reduced the number of jobs suitable for an unskilled workforce. At The Ami Foundation, we are interested in experiments that have helped young people to complete their education, or those who have dropped out to get back into education.

Thirdly, it is important to ensure cooperation between different organisations, such as employment services, social and health services, and youth work. The problems underlying the NEET status are complex and require multidisciplinary cooperation. According to a survey by the Finland Chamber of Commerce, young people’s well-being and mental health challenges reduce productivity within businesses. In addition to promoting youth employment, it is important to develop effective ways to reduce long-term unemployment among other age groups. As of 2025, new Finnish employment areas have the opportunity to create more effective measures to improve the situation of the long-term unemployed, and to increase local understanding of the target group.

Sources and literature

- Bouget Denis, Vanhercke Bart: Tackling long-term unemployment in Europe through a Council Recommendation? Social policy in the European Union: state of play 2016.

- Elonen, N., Niemelä, J., Saloniemi, A. (2017). Aktivointi ja pitkäaikaistyöttömien monenlainen toimijuus. (Activation and multiple agency of the long-term unemployed.) Janus Sosiaalipolitiikan ja sosiaalityön tutkimuksen aikakauslehti, 25(4), 280-296.

- ETLA: Teknologisen kehityksen vaikutus työllisyyteen. (Impact of technological development on employment.) 2021.

- Eurostat: Long-term unemployment (12 months and more) by sex, age, educational attainment level and NUTS 2 region (%).

- Ylistö Sami: Miksi työnhaku ei kiinnosta? Nuorten pitkäaikaistyöttömien työnhakuhaluttomuudelle kertomia syitä. (Why is job search not interesting? Reasons given by young long-term unemployed people for not wanting to look for a job.) Työelämän tutkimus. 13 (2) 2015.

- National Audit Office of Finland: Pitkäaikaistyöttömien työllistyminen ja syrjäytymisen ehkäisy. (Employment and exclusion prevention for the long-term unemployed.) Tuloksellisuustarkastuskertomus 229/2011.

- Redmond Paul, McFadden Ciara: Young People Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET): Concepts, Consequences and Policy Approaches. The Economic and Social Review, Vol. 54, No. 4 Winter 2023, pp. 285-327.

- Hanhijoki Ilpo: Koulutuksen ja työvoiman kysyntä 2035. Osaamisen ennakointifoorumin ennakointituloksia tulevaisuuden koulutustarpeista. (Education and labour demand 2035. Results from the Skills Forecasting Forum on future training needs.) Finnish National Agency for Education, Reports and Studies 2020:6.

- Hiilamo Heikki, Määttä Anne, Koskenvuo Karoliina, Pyykkönen Jussi, Räsänen Tapio, Aaltonen Sanna: Nuorten osallisuuden edistäminen. Selvitysmiehen raportti. (Promoting youth inclusion. Rapporteur’s report.) Diaconia University of Applied Sciences 2017.

- Nichols Austin, Mitchell Josh, Lindner Stephan: Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment, The Urban Institute 2013.

- Maunu Tallamaria, Räisänen Heikki, Tuomaala Mika: Pitkä työttömyys. (Long unemployment.) Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland analyses 114/2023.

- Statistics Finland: Unemployment statistics.

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland, Employment Statistics: Unemployed jobseekers by duration of unemployment at the end of the month.

- Kerätär Raija: Pitkäaikaistyöttömät ja työkykyä ylläpitävän toiminnan tarve. (The long-term unemployed and the need for activities supporting the fitness for work.) Lääkärilehti 14/1995.

- Press release from the Finland Chamber of Commerce 20 May 2024.

- Nikolova Milena, Nikolaev Boris: How having unemployed parents affects children’s future well-being. Brookings 2018.