THIS BLOG’S THEME: INVOLUNTARY PART-TIME WORK

The number of people engaged in involuntary part-time work should be significantly lower than today, for the Finnish capital region to have the best labour market in the Nordic countries in the future.

The state of and changes in the labour market are often assessed on the basis of unemployment and employment trends. In the light of these two important indicators, the Finnish capital region has lagged behind other Nordic capital regions for years.

Employment statistics do not tell us what and how much people actually work, as Statistics Finland counts as employed even the people who work very few hours.

To better understand the functioning of the labour market, attention should be paid to involuntary part-time work. In public debate, this statistic is neglected.

Reluctant part-time work weakens well-being

The Ami Foundation’s vision [RM1] is for the Finnish capital region to have the best labour market in the Nordic countries. The number of reluctant part-time workers should therefore be significantly lower than today.

To change this, the economic situation of employers should evolve in a direction where full-time work is available to all who seek it.

Employers should also invest in training and promotion opportunities for part-time workers, as well as in their ability to influence their working hours. This will reduce the negative impact of involuntary part-time work on people’s well-being and job satisfaction, which is also one of the priorities in The Ami Foundation’s programme.[RM2]

Part-time work has its place, and it suits many people’s life situations very well. For example, studies, health reasons, or caring responsibilities are factors that can be behind a self-selected part-time job. Many employers need part-time workers, and students, for example, are an important source of labour in many sectors. There are also part-time workers among those on old-age pension.

Reluctant part-time work is not your choice

The opposite of self-selected part-time work is involuntary part-time work, where the worker would like to move to full-time work but without success. In other words, the worker is involuntarily forced to work less than they would like to.

Part-time work is a better option than unemployment, as it can act as a gateway to full-time work. It also provides valuable work experience.

However, involuntary part-time work has increased across Europe since the 2008–2009 financial crisis (Green, Livanos 2015), and the phenomenon deserves attention due to its negative effects.

Part-time work exposes to unemployment

Technological developments have also been shown to increase part-time work and hence involuntary part-time work (Van Doorn, Van Vliet 2022). This contributes to the need to address the side effects of involuntary part-time work, as rapid technological developments such as Artificial Intelligence are changing jobs and the nature of work.

Research shows that involuntary part-time work has negative effects on the development potential of a worker. People in involuntary part-time jobs have fewer opportunities to participate in training, narrower career prospects, and fewer opportunities to learn and develop on the job, compared to permanent and full-time employees. (Kauhanen, Nätti 2011.)

The increase in involuntary part-time work since the 2010s can also be seen as a cause for concern, as some statistics show a downward trend in skills development among the adult population.

Part-time work exposes people to unemployment, challenges in supporting oneself, and repeated short-term employment. Those who work part-time involuntarily are also less satisfied with their working conditions. In the long run, reluctant part-time workers may end up as discouraged job seekers, which affects their productivity (Ruttiya, Ikemoto 2014).

The link between poverty and involuntary part-time work

Part-time workers often accumulate evening, night, shift, and weekend work, which can be associated with negative consequences for their well-being, especially in the case of involuntary part-time work (Ojala, Nätti, Kauhanen 2014). Indeed, involuntary part-time work is clearly associated with in-work poverty (Jakonen, Säilävaara, Ikonen 2023).

In Finland, non-Finnish or Swedish speakers are overrepresented among involuntary part-time workers (Ojala, Pyöriä, Jakonen 2024).

This reinforces the perception of people from a foreign background as a second-class workforce. It increases ethnic segregation in the labour market. The problem is also cumulative, as studies show that low socio-economic status has an intergenerational effect (Eskelinen, Erola, Karhula, Ruggera, Sirniö 2020).

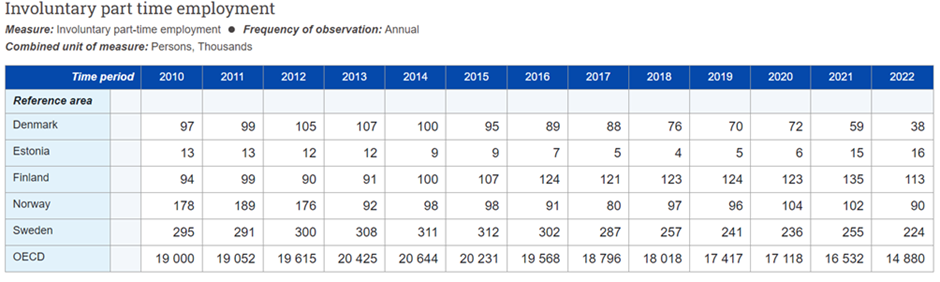

Numbers have increased in both Finland and Estonia

Involuntary part-time work is also about gender equality in working life. Women work more part-time than men, suggesting that involuntary part-time work is more common among women than men. Gender segregation does not fully explain the prevalence of part-time work for women compared to men, as, according to Statistics Finland, women are overrepresented in part-time work also in some industries where there are as many men as women (Lukkarinen 2018).

The number of involuntary part-time workers has increased in Finland since the early 2010s, and a similar trend can be seen in Estonia.

In Denmark and Norway, on the other hand, the number of involuntary part-time workers has fallen significantly. In Sweden, the numbers in 2022 were lower than in the early 2010s. On the positive side, in Finland, the figures have been on a downward trend compared to the peak years of involuntary part-time work (Figure 1).

Finland has a lot of work to do

According to statistics published by Eurostat, the share of involuntary part-time workers of all part-time workers in Finland has, over the last ten years, remained the highest in The Nordics (Pohjola in Finnish), comprising the Nordic Countries and Estonia (Tallinn), when examining the age group 20–64.

In 2023, Finland’s share was 26.6%, while Denmark’s had the lowest share in The Nordics at 7.6%. By producing and analysing comparative data, we can gain a deeper insight into where Finland needs to improve on its way to becoming the best labour market in the Nordic countries.

This becomes interesting when we compare the share of reluctant part-time workers in the 15–29 age group. In this age group, the share of involuntary part-time workers in 2023 was 24% in Sweden and 18.8% in Finland.

At the same time, Sweden had the lowest share of NEETs, youth not in employment, education or training. Looking at the youth age group, Denmark also has the lowest share of young people in part-time employment among its peers at 7.1% (Figure 2).

Fewer involuntary part-time workers in Helsinki Metropolitan Area than rest of Finland

There are no statistics on the share of involuntary part-time workers exclusively for the four municipalities in the Finnish capital region. Instead, we can compare the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region with the Danish capital region Region Hovedstaden.

According to data from Statistics Finland, in Helsinki-Uusimaa, 21.70% of all part-time workers aged 15–74 worked part-time because there was no full-time work available in 2023.

The difference with the Danish capital region is significant, as the corresponding figure for the Region Hovedstaden was only 6.1%, according to data provided by the Danish statistics authorities.

Indeed, these data show that involuntary part-time work is significantly more common in the Finnish capital region than in Copenhagen. On the positive side, however, the figure is lower in the Finnish capital region than in the rest of Finland.

Sources

- Choi Hyeri, Marinescu Ioana: The Labor Demand Side of Involuntary Part-time Employment, APPAM Fall Research Conference, 2022.

- Eskelinen Niko, Erola Jani, Karhula Aleksi, Ruggera Lucia, Sirniö Outi: Eriarvoisuuden periytyminen. (Inheritance of inequality) In Eriarvoisuuden tila Suomessa 2020, edited by Maija Mattila, 2020.

- Eurofound: Labour market slack

- Green Anne, Livanos Ilias: Involuntary non-standard employment in Europe, European Urban and Regional Studies, 24(2), 175–192. 2017

- Jakonen Mikko, Säilävaara Jenny, Ikonen Hanna-Mari: Työssäkäyvien köyhien kokemuksia prekaarista työstä ja sosiaaliturvasta 2000-luvun Suomessa. (Experiences of the working poor of precarious work and social security in 21st century Finland.) Työväentutkimus vuosikirja. Vol 37 (2023).

- Kauhanen Merja: Osa-aikatyö yksityisillä palvelualoilla. (Part-time work in the private service sector.) Labore 2016.

- Kauhanen Merja, Nätti Jouko: Involuntary temporary and part-time work, job quality and well-being at work. Labore 2011.

- Lukkarinen Henri: Vastentahtoiset osa-aikatyöt yleistyneet 2010-luvulla. (Reluctant part-time work has become more common in the 2010s.) Statistics Finland. 2018.

- OECD: Involuntary part-time employment.

- Ojala Satu, Pyöriä Pasi, Jakonen Mikko: Maahanmuuttajat prekaarina työvoimana. (Immigrants as a precarious labour force.) Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland 2024.

- Ojala Satu, Nätti Jouko, Kauhanen Merja: Työn laatu ja myöhempi työura osa- ja määräaikaisessa työssä. (Quality of work and later career in part-time and fixed-term work.) Palkansaajien tutkimuslaitos. 2015.

- Outi Toivanen-Visti: Työtätekevien köyhyys on lisääntynyt ja se tulee kalliiksi yhteiskunnalle – yksilölle se on kuin elämä jäisi odotustilaan. (In-work poverty has increased and it is costly for society – for the individual it is like being stuck in a waiting room.) MustRead. 2019.

- Ruttiya Bhula-or, Ikemoto Yukio: Factors Affecting Involuntary Part-time Employment in OECD Countries. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. Vol 3(2). 2014.

- SAK: Työsuhteen jatkuva tila ei voi olla epävarmuus. (The permanent state of an employment relationship cannot be insecurity.)

- Van Doorn Lars, Van Vliet Olaf: Wishing for More: Technological Change, the Rise of Involuntary Part-Time Employment and the Role of Active Labour Market Policies, Journal of Social Policy, published online 2022:1–21.