As a result of technological progress, jobs and even entire professions have disappeared and will inevitably continue to disappear in the future. At the same time, development of artificial intelligence and robotics, among other things, are creating new jobs and transforming old ones. For example, technological innovations and their product development alongside the maintenance, monitoring, and servicing of machines and systems are creating new job opportunities. New technologies can be utilised in almost all occupational sectors, which in turn requires the existing workforce to be ready and adaptable to adopt new software or equipment, and to be trained to use it. Good basic training is key to responding to changing skills needs.

The role of education becomes crucial

According to the Finnish Education and Labour Demand 2035 Report, the growth in labour demand will particularly impact people with higher education, with most jobs opening up in professional and managerial roles. At the same time, the share of low-skilled jobs will decrease (Hanhijoki 2020). This change is already visible in the labour market, as the relative employment share has increased in the occupational categories of managers, specialists, and experts, while the declining occupational categories have been office and customer service workers, and various manufacturing and construction occupations (ETLA 2021). The secretarial profession illustrates this trend well: this occupation has long been characterised by an oversupply of applicants, as shown by the Labour Force Barometer data.

The Helsinki-Uusimaa Region, including the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, is undoubtedly the driving force of the Finnish economy, as half of Finland’s economic growth in the 2000s has been generated in Helsinki-Uusimaa. The region’s productivity is higher than in the rest of Finland, partly due to the high level of education and skills of its workforce. The capital region and Helsinki-Uusimaa as a whole compete with other metropolitan areas, such as the large coastal cities of the Baltic Sea, for investment, skilled labour, and research. To ensure the economic success of the Helsinki Metropolitan Area and Finland as a whole, it is particularly important to ensure that the education and skills of our workforce remain at the same level as those of our competitor regions. We also need to ensure that the proportion of people without a post-primary education qualification declines, and that the proportion of highly educated people rises to the level of our peer regions.

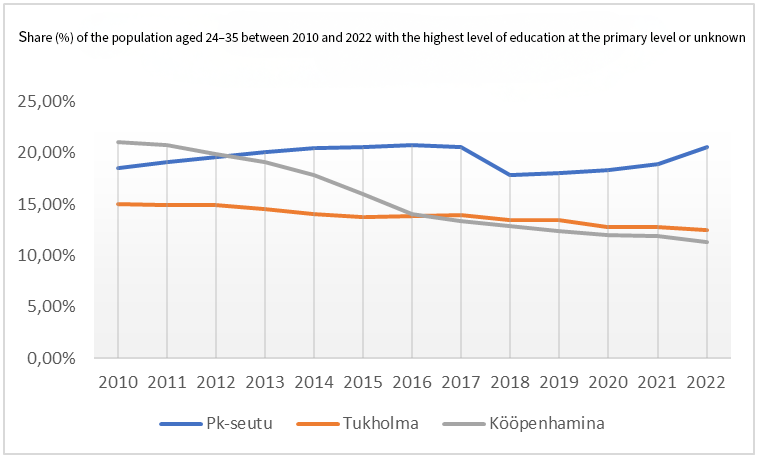

According to the City of Helsinki Executive Office’s Urban Research and Statistics Unit, the proportion of young people with primary education only has started to increase (Ahtiainen 2024). The same trend can be seen throughout the metropolitan area while, in comparison, in areas such as Stockholm County and Region Hovedstaden in Copenhagen the trendline is still going downwards (Figure 1). The data are based on national statistics, and may include differences in the compilation of the statistics between countries. Differences between countries may also be related to the recognition of immigrants’ qualifications, which in itself would be an interesting area of study for a Nordic comparison. However, it is worth noting that the proportion of people without a post-primary education qualification is decreasing in Stockholm and Copenhagen, while in Finland it is increasing among young people. At the same time, it is important to note that the share of highly educated people has lagged behind Stockholm and Copenhagen, regardless of whether we compare the four municipalities in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area or the whole of the Helsinki-Uusimaa Region.

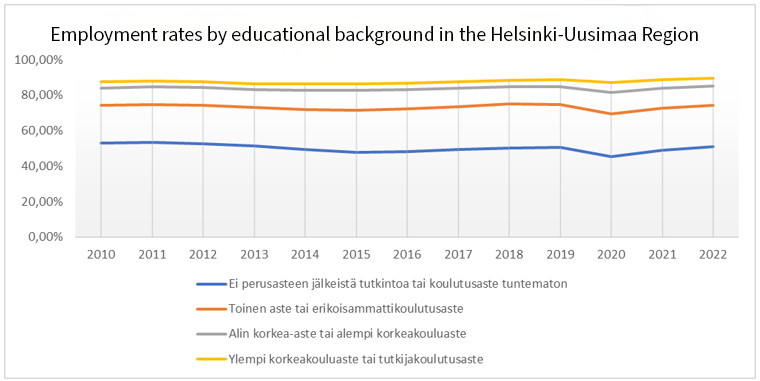

During 2024, we have read in the media about the increased unemployment rates of highly educated people, and the challenges experienced by recent graduates to find employment in their field (e.g., Haajanen 20/7/2024). The current weak economic situation is undeniably challenging, and it is also reflected in the labour market for highly qualified people. The debate on finding a job that matches your education is an important topic that deserves its own blog post. However, from a broader perspective, we know that education protects against unemployment and raises salary levels. Statistics show that the higher the level of education is, the higher the employment rate (Figure 2).

Legend for the chart:

- Ei perusasteen jälkeistä tutkintoa tai koulutusaste tuntematon = No post-primary education degree or unknown level of education.

- Toinen aste tai erikoisammattitutkinto = Upper secondary education or special vocational degree.

- Alin korkea-aste tai alempi korkeakoulututkinto = Lower tertiary education or lower university degree.

- Ylempi korkeakouluaste tai tutkijakoulutusaste = Higher university degree or PhD degree.

The 2022 statistics on salaries in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area provided by Statistics Finland also show that education has a positive effect on salary levels. This is not only the case for higher education, but also for vocational labour market training which raises the employment and income levels of those who participate in the education (Alasalmi, Busk et al. 2022). Between 2009 and 2021, the employment rate of those with special vocational and professional qualifications was clearly higher than for those with a vocational qualification (Hievanen, Goman et al. 2024). Data we compiled earlier this spring also show that participation in adult education and training related to work or occupation is more common among those with higher education.

A look at NEET youth

Education is key to the competitiveness of the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. In The Ami Foundation’s programme, matching skills and needs is one of our priorities. The Ami Foundation is particularly interested in research that can deepen our understanding of educational segregation, and identify concrete solutions to effectively address the problem. We also want to promote projects that can turn segregation trends in a more positive direction.

Data from the Education Administration’s statistical service Vipunen show that upper secondary school education is gender-segregated in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, with boys preferring vocational education. At the same time, foreign-language students are under-represented in upper secondary school education in relation to the size of the population group. These factors are strongly linked to the fact that women are more likely than men to complete higher education degrees and that Finns with an immigrant background are under-represented in higher education. Of national concern are also regional disparities in education, for example, between provinces (on regional disparities, see e.g. Kalenius 2023). Language and gender differences are also reflected in drop-out rates from upper secondary education.

Among youth not in employment, education or training (NEET), men are over-represented in the Helsinki Metropolitan area, and NEET status is more common among those with foreign backgrounds than those with Finnish backgrounds. Poor educational attainment has an intergenerational impact; parents’ school drop-out predicts children’s school drop-out. Other forms of deprivation, such as income support and unemployment, have also been found to have an intergenerational effect (Erola, Kallio, Vauhkonen 2017). Parental educational attainment also has an effect in the other direction, as higher parental education predicts higher educational attainment for children (Keski-Petäjä, Witting 2016).

By promoting young people’s successful attachment to education and employment, we prevent the accumulation of problems, challenges to employment later in life, and the transmission of intergenerational problems. At the same time, we can unlock the potential of more young people, and reduce NEET rates.

Raising educational attainment and reducing uneducation are key to the development of the Helsinki Metropolitan Area to meet changing skills needs. At the same time, we need to address the legacy of low education and low socio-economic status to prevent greater educational and labour market segregation, and regional segregation.

Sources and literature

- Ahtiainen Hanna: Perusasteen varassa olevien nuorten osuus kääntyi kasvuun – nuorten koulutus Helsingissä 2023. (The proportion of young people with primary education only has started to increase – education of young people in Helsinki 2023.) City Executive Office’s Urban Research and Statistics Unit. 2024.

- Danmarks Statistik: Folketal den 1. i kvartalet efter område, alder og tid. Statistical data.

- Danmarks Statistik: Population’s højest fuldførte uddannelse (15-69 år) efter bopælsområde, højest fuldførte uddannelse, socioøkonomisk status, branche, alder og køn. Statistical data.

- European Commission: The labour market impact of robotisation in Europe.

- Great place to work: Tekoäly työelämässä: miten tukea työntekijöitä AI:n murroksessa? (AI at work: how to support workers in the AI revolution?)

- Alasalmi Juho, Busk Henna, Holappa Veera, Karhunen Hannu, Mayer Minna, Nivala Annika, Suhonen Tuomo, Valtakari Mikko: Ammatillinen työvoimakoulutus nostaa työllisyyttä ja tuloja – lisää tietoa sekä ohjausta tarvitaan. (Vocational labour market training increases employment and income – more information and guidance needed.) Government’s analysis, assessment and research activities 2022.

- Erola Jani, Kallio Johanna, Vauhkonen Teemu: Ylisukupolvinen kasautuva huono-osaisuus Turussa ja muissa Suomen suurissa kaupungeissa. (Intergenerational accumulating deprivation in Turku and other large Finnish cities.)

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland: Share of NEET youth 1995–2022. Integration database. Statistical data.

- Hanhijoki Ilpo: Koulutus ja työvoiman kysyntä 2035. (Education and labour demand 2035.) Finnish National Agency for Education 2020.

- Kalenius Aleksi: Sivistyskatsaus 2023. (Bildung Review 2023.) Ministry of Education and Culture 2023.

- Keski-Petäjä Miina, Witting Mika: Vanhempien koulutus vaikuttaa lasten valintoihin. (Parents’ education affects children’s choices.) Statistics Finland 2016.

- ETLA: Teknologisen kehityksen vaikutus työllisyyteen. (Impact of technological development on employment.) 2021.

- Hievanen Raisa, Goman Jani, Hiltunen Kirsi, Hakamäki-Stylman Veera: Katsaus ammatillisen tutkinnon suorittaneiden työllistymiseen. (Overview of the employment of VET graduates.) KARVI 2024.

- Haajanen Eino: Aiemmin turvallisilta aloilta valmistutaan nyt työttömiksi – ”Rehellisesti sanottuna ahdistaa”. (Graduates from previously secure fields now unemployed – “Honestly, it’s distressing”.) Helsingin Sanomat 20 July 2024.

- Pyykkönen Jussi: Tutkinto ‒ varmin tie työllisyyteen. (A degree is the surest way to employment.) Ajatuspaja Visio publications 1/2022.

- Statistiska centralbyrån: Befolkning 16–95+ år efter region, utbildningsnivå, ålder och kön. År 2008–2023. Statistical data.

- Statistiska centralbyrån: Folkmängden efter region, civilstånd, ålder och kön. År 1968 – 2023. Statistical data.

- Statistics Finland: 15 vuotta täyttänyt väestö koulutusasteen, kunnan, sukupuolen ja ikäryhmän mukaan, 1970–2022. (Population over 15 by educational level, province, gender and age group, 1970–2022.)

- Statistics Finland: Salary structure statistics 2022. Statistical data commissioned by The Ami Foundation for Helsinki Metropolitan Region as a paid subscription.

- Statistics Finland: Employment Statistics. Population by region, main activity, level of education, gender, age and year, 1987–2022.

- Helsinki-Uusimaa Regional Council: Uudenmaan elinkeinorakenne tarjoaa erinomaiset edellytykset talouden kasvulle. (The economic structure of Helsinki-Uusimaa offers excellent conditions for economic growth.)